Jesus on Trial: A Lawyer Affirms the Truth of the Gospel

David Limbaugh is not a passive observer—he is a passionate persuader. Readers of his twice-weekly columns, or his several best-selling books know that he has less concern with detached or bemused reflections, but rather is out to win hearts and minds with calls to urgency.

So why is this attorney and law professor, and essayist of public affairs, turning his attention from contemporary law and politics to matters of timeless theology? Why does he devote his considerable rhetorical talents, against his own admitted ambivalence, to persuade—affirm—a belief that even some of our nation’s Founders were content to relegate to the purely private sphere?

Mr. Limbaugh has tackled religion before, from a political perspective, in Persecution: How Liberals are Waging War Against Christians (2003). If not an outright “sequel”, Jesus on Trial is at least a natural follow-up to Persecution: after all, if the best defense is the truth, then our response to the crisis—the “war” against Christianity (and our free society)—will be served better if we are more confident in the truth of Christianity’s core proposition. “Christianity undergirds, rather than undermines our freedoms,” asserted Mr. Limbaugh in Persecution. “Indeed, Christian precepts formed the intellectual underpinnings of American constitutional government….Christians committed to their faith and to American freedom have an unmistakable right, if not a duty, to engage in the political arena and to seek to influence the course of this country.”

Mr. Limbaugh now invokes that earlier duty along with the truth in his opening chapter of the newer book: “Those interested in truth have a duty to defend the faith and the Christian worldview.” How well does he succeed?

In Christian writing, the apologia frequently complements the confession, which for Mr. Limbaugh is the memoir of his own journey from skeptic or outright “nonbeliever” to an enthusiastic practitioner and teacher of Christian doctrine. By documenting his own learning, Mr. Limbaugh presents a readable and invaluable survey of the literature.

In Jesus on Trial, Mr. Limbaugh seamlessly alternates between a personal intellectual narrative and a “research-paper style” exposition of the arguments that persuaded him—not just the assertions of dozens of fellow apologists, but more importantly the Gospels, Epistles, and other Scriptural sources themselves. These two approaches reinforce each other in making credible the twin sources of our knowledge-in-faith, learning and experience: “I believe I can relate to skeptics, having been one for many years. I don’t look down on skeptics; in fact I believe I understand their perspective. But I also know that nonbelievers don’t have to remain that way. The Holy Spirit beckons all to come to Jesus Christ in faith.”

It is particularly important to Mr. Limbaugh’s case to demonstrate that the Gospels are consistent with a logically cohesive and unified Scriptures as a whole—he devotes four chapters to “The Amazing Bible”, leading us through “Unity”, “Prophecy”, “Reliability and Internal Evidence”, and “Reliability and External Evidence”.

Mr. Limbaugh presents the Bible as unique in the world’s canonical religious texts for having “one connected story”, a historical story with real human actors and places, not just of salvation history but of God’s revelation of “Who He is and His desire that we have a relationship with Him.”

But knowing that some skeptics will demand more than just this literary consistency, Mr. Limbaugh outlines across two chapters the evidence for his contention, “When compared to any other ancient document or book, by any fair measure, the Bible acquits itself—objectively—as more historically reliable.”

If any one chapter were to stand as an independent essay—and resonate with the conservative audience—it would be “Truth, Miracles, and the Resurrection of Christ”. The social-moral implications are stark and ominous— “Ultimately, postmodernism leads to intellectual chaos and, if its roots are planted deeply enough, moral anarchy.”

But if the contemporary cultural assault on objective truth and morality—begun first through modernism’s misguided embrace of moral relativism at the expense of Christian authority, and then extended by the postmodernist assault on “the objectivity of truth and the universality of reason” itself—is to be resisted successfully, then those who, like Mr. Limbaugh, believe in the Christian foundation of our social-moral code will have to answer this: “A postmodern approach says the Bible is true to the extent that it is found meaningful or spiritually inspiring for the individual believer, but not in any kind of objective sense….”

Mr. Limbaugh concedes the difficulty of his task when he admits, “I can’t imagine many people reasoning their way to believing in God’s existence if they are predisposed against believing”; nonetheless, he mounts his defense first within the classic philosophical frameworks of cosmology, teleology, and morality. If then there exists a God capable of miracles, can we accept as objectively true that some reported miracles—most essentially the Resurrection—actually happened? Can the Resurrection be proven from physical and historical evidence?

Here Mr. Limbaugh takes us on a journey through centuries of competing philosophical and critical skepticism and belief (it is no small task to take on Spinoza and Hume), and each reader will have to judge for him or herself whether the possibility of miracles is or is not a better explanation than all others (and if the moral claims of Christianity thus will hold up).

The weakest chapter of Jesus on Trial is when Mr. Limbaugh attempts to dispute theories of Darwinian macroevolution in favor of “Intelligent Design” or other alternate explanations (“Science Makes the Case—for Christianity”), mainly because these are not arguments that need to be made in affirming the truth of the Gospel. His motives are worthy—to defend Christianity from the calumnies that its adherents “are uninterested in truth or in science”, and to establish the fact that “science and Christianity are perfectly compatible and mutually supportive”. But whatever logical or evidentiary problems there may have been in some theories of evolution or the origins of life and the material universe, these points of contention likely will not be resolved to every reasonable satisfaction in a mere thirty pages (which Mr. Limbaugh sort of concedes), and are at risk of distracting from the proclamation of “the Good News”.

In Jesus on Trial, Mr. Limbaugh shares his own long and difficult encounter with us. He backs up his scholarship with a hefty fifty pages of endnotes, and this is where we see the method and manner of a lawyer at work. Think of Jesus on Trial in format as a “legal brief”—but instead of a compilation of statutory law, case law, and law-review commentary, woven with the lawyer’s own argumentative analysis, including the refutation of actual or possible objections, Jesus on Trial instead is a compendium of other authorities: Scriptures, apologists and other theologians, and occasional opposing voices, unified not only with sharp analysis but also a personal testimony that imbues a relevance for each who dares to seek this particular truth.

If a legal brief is done rightly and with integrity, and presented in an honest and competent court of law, a true and just verdict will be rendered. Likewise, through Jesus on Trial, Mr. Limbaugh is entrusting our culture and society with being that “courtroom” where his theological arguments will succeed or fail on their merits, for better or for worse—and perhaps with as much consequence. “Apologetics, examining evidence, or reason alone can’t save us. It can only get us to the point of faith.” Even if after reading Mr. Limbaugh’s book you still don’t fully agree with the truth of the Gospel, it surely will be harder not to respect its claims a little more.

Original CBC review by D.C. Alan. D. C. Alan is a writer, musician, and artist in the nation’s capital.

Tags: David Limbaugh, Jesus on Trial: A Lawyer Affirms the Truth of the Gospel

- The Author

David Limbaugh

** Exclusive CBC Author Interview with David Limbaugh ** David Limbaugh is a lawyer, nationally syndicated columnist, political commentator, and author […] More about David Limbaugh.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

VIP BONUS Episode – “One Last Thing” with David Limbaugh As He Discusses “Growing Up Limbaugh”!

Listen to our exclusive bonus podcast interview with David Limbaugh as he talks about growing up in the Limbaugh household! [...]

Ep. 38 – David Limbaugh Interview: How Did the Early Christian Church Form?

Our friend David Limbaugh is back in the CBC studios to discuss his new book, Jesus is Risen: Paul and[...]

David Limbaugh’s Top 5 Favorite Books Every Conservative Should Read

David Limbaugh, brother of Rush Limbaugh, is a bestelling author of Christian apologetics -- including The Emmaus Code and the[...]

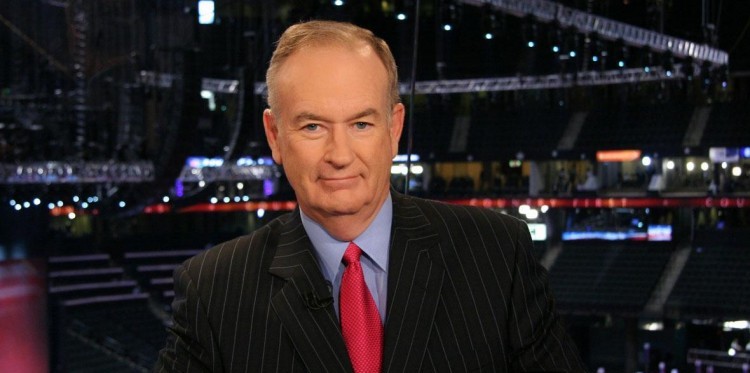

Bill O’Reilly Latest Victim of NYT “Best Sellers” List Deception

The NYT has been exposed once again for deceiving the American public with its hardcover nonfiction “Best Sellers” list -[...]

Limbaugh Brothers Dominate Conservative Bestseller List

The dynamic duo of this week’s Conservative Bestseller List are the Brothers Limbaugh - both landing a total of three[...]

Ratings Details