1984

James Joyce, in the person of Stephen Dedalus, made a now famous distinction between static and kinetic art. Great art is static in its effects; it exists in itself, it demands nothing beyond itself. Kinetic art exists in order to demand; not self-contained, it requires either loathing or desire to achieve its function. The quarrel about the fourth book of ”Gulliver’s Travels” that continues to bubble among scholars — was Swift’s loathing of men so great, so hot, so far beyond the bounds of all propriety and objectivity that in this book he may make us loathe them and indubitably makes us loathe his imagination? — is really a quarrel founded on this distinction.

It has always seemed to the present writer that the fourth book of ”Gulliver’s Travels” is a great work of static art; no less, it would seem to him that George Orwell’s new novel, ”Nineteen Eighty-four,” is a great work of kinetic art. This may mean that its greatness is only immediate, its power for us alone, now, in this generation, this decade, this year, that it is doomed to be the pawn of time. Nevertheless it is probable that no other work of this generation has made us desire freedom more earnestly or loathe tyranny with such fulness.

”Nineteen Eighty-four” appears at first glance to fall into that long-established tradition of satirical fiction, set either in future times or in imagined places or both, that contains works so diverse as ”Gulliver’s Travels” itself, Butler’s ”Erewhon,” and Huxley’s ”Brave New World.” Yet before one has finished reading the nearly bemused first page, it is evident that this is fiction of another order, and presently one makes the distinctly unpleasant discovery that it is not to be satire at all.

In the excesses of satire one may take a certain comfort. They provide a distance from the human condition as we meet it in our daily life that preserves our habitual refuge in sloth or blindness or self-righteousness. Mr. Orwell’s earlier book, ”Animal Farm,” is such a work. Its characters are animals, and its content is therefore fabulous, and its horror, shading into comedy, remains in the generalized realm of intellect, from which our feelings need fear no onslaught. But ”Nineteen Eighty-four” is a work of pure horror, and its horror is crushingly immediate.

The motives that seem to have caused the difference between these two novels provide an instructive lesson in the operations of the literary imagination. ”Animal Farm” was, for all its ingenuity, a rather mechanical allegory; it was an expression of Mr. Orwell’s moral and intellectual indignation before the concept of totalitarianism as localized in Russia. It was also bare and somewhat cold and, without being really very funny, undid its potential gravity and the very real gravity of its subject, through its comic devices. ”Nineteen Eighty-four” is likewise an expression of Mr. Orwell’s moral and intellectual indignation before the concept of totalitarianism, but it is not only that.

It is also — and this is no doubt the hurdle over which many loyal liberals will stumble — it is also an expression of Mr. Orwell’s irritation at many facets of British socialism, and most particularly, trivial as this may seem, at the drab gray pall that life in Britain today has drawn across the civilized amenities of life before the war.

In 1984, the world has been divided into three great super-states — Eastasia, Eurasia, and Oceania. Eurasia followed upon ”the absorption of Europe by Russia,” and Oceania, ”of the British Empire by the United States.” England is known as Airstrip One, and London is its capital. The English language is being transformed into something called Newspeak, a devastating bureaucratic jargon whose aim is to reduce the vocabulary to the minimum number of words so that ultimately there will be no tools for thinking outside the concepts provided by the state.

Oceania is controlled by the Inner Party. The Party itself comprises 25 per cent of the population, and only the select members of the Inner Party do not live in total slavery. The bulk of the population is composed of the ”proles,” a depraved mass encouraged in a gross, inexpensive debauchery. For Party members, sexual love, like all love, is a crime, and female chastity has been institutionalized in the Anti-Sex League.

Party members cannot escape official opinion or official observation, for every room is equipped with a telescreen that cannot be shut off; it not only broadcasts at all hours, but it also registers precisely with the Thought Police every image and voice; it also controls all the activities that keep the private life public, such as morning calisthenics beside one’s bed. It is the perpetually open eye and mouth. The dictator, who may or may not be alive but whose poster picture looks down from almost every open space, is known as B. B., or Big Brother, and the political form is called Ingsoc, the Newspeak equivalent of English socialism.

One cannot briefly outline the whole of Mr. Orwell’s enormously careful and complete account of life in the super-state, nor do more than indicate its originality. He would seem to have thought of everything, and with vast skill he has woven everything into the life of one man, a minor Party member, one of perhaps hundreds of others who are in charge of the alteration of documents necessary to the preservation of the ”truth” of the moment.

Through this life we are instructed in the intricate workings of what is called ”thoughtcrime” (here Mr. Orwell would seem to have learned from Koestler’s ”Darkness at Noon”), but through this life we are likewise instructed in more public matters such as the devious economic structure of Oceania, and the nature and necessity of permanent war as two of the great super-states ally themselves against a third in an ever-shifting and ever-denied pattern of change. But most important, we are ourselves swept into the meaning and the means of a society which has as its single aim the total destruction of the individual identity.

To say more is to tell the personal history of Winston Smith in what is probably his thirty-ninth year, and one is not disposed to rob the reader of a fresh experience of the terrific, long crescendo and the quick decrescendo that George Orwell has made of this struggle for survival and the final extinction of a personality. It is in the intimate history, of course, that he reveals his stature as a novelist, for it is here that the moral and the psychological values with which he is concerned are brought out of the realm of political prophecy into that of personalized drama.

”Nineteen Eighty-four,” the most contemporary novel of this year and who knows of how many past and to come, is a great examination into and dramatization of Lord Acton’s famous apothegm, ”Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Book Review from The New York Times, by Mark Schorer

Tags: 1984, Big Brother, George Orwell

- The Author

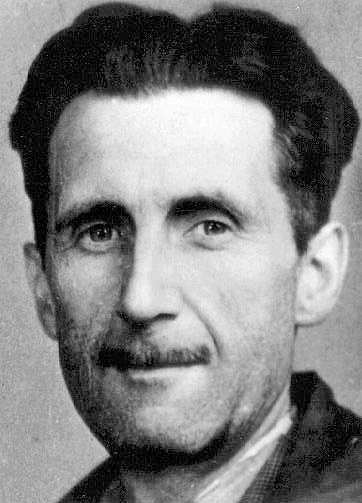

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair, who used the pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist and critic. His work […] More about George Orwell.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

The Top Five Anticommunist Books Ever Written

The Soviets collapsed in 1991. Communism, it seems, is on its last legs in today's 21st century world. But conservatives[...]

Ratings Details