Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address Illustrated

It is a book filled with the images of sons.

Terrible images, some taken by the famous Civil War photographer Matthew Brady. Young men, barely out of boyhood, dead on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Here is the young man, his thick dark hair tousled, rifle and cap nearby. Eyes closed, he lies alone, amidst the jutting hillside rocks. Over there, on the flatness of open ground, lies a seemingly older man, mouth forming an open circle of death. He is not alone, some nineteen others joining him in the general vicinity. Side by side he died with the other nineteen — but no one knows whether this was Smith from Massachusetts, O’Brien from New York or Lunt from Vermont. Names that appear in another photograph as the headstones that dot the countryside began, mercifully, to appear in an order that belies the chaos of slaughter that brought their need.

We do know they were all sons. Husbands, perhaps. Fathers, maybe. But all were sons.

Captured in the black and white beginnings of photography, bodies bloating in the July heat, the heartrending images assembled by Jack E. Levin in his book Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address Illustrated are a vivid reminder of what it took to ensure that America would be a nation built on the ideals of liberty and freedom.

These are the men who fought for the idea that their rights came not from, as John F. Kennedy would later say, “the generosity of the state but the hand of God.” Descendent sons literal and figurative, native-born and immigrant-born, of those devoted to the principles written into the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. They are the 19th century incarnation of those first famous American sons who called themselves the Sons of Liberty.

This third Sunday of June, Americans will celebrate Father’s Day, an American tradition since the early 20th century. Eleven days later, the small town some thirty miles from where this is written will commemorate once again the murderous battle that raged on its neighboring fields for three days. Some 51,000 American sons of fathers were casualties over the course of those three days, a battle memorialized the following November when Abraham Lincoln traveled to Pennsylvania from Washington to dedicate the sacred ground under which so many of these men were buried.

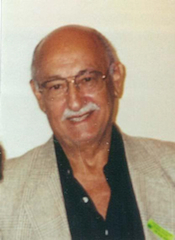

Jack E. Levin, now 85, the father of radio-talk show host Mark Levin, decades ago took the time to compile a book to celebrate an immigrant son’s love for his country — and Lincoln’s clarion call for liberty, equality and freedom. Now re-released with its original 1965 foreword, this small, poignant book could not have re-appeared at a better time.

Every day, so it seems, the very essence of the American idea is challenged by those with agendas both suspect and disturbing.

There are those who wish to replace a country devoted to principles of freedom and liberty with a country devoted to judging others by race. For some the Constitution itself would be eviscerated, the rule of law vanquished in this or that locale by Islamic sharia. Free speech would be transformed into the Orwellian “hate speech” — with government bureaucrats deciding what is or is not acceptable to say for fear of giving offense to this, that or the other group financed by a rich man’s money.

Laws written to expressly forbid the exchange of high office for political favors are dismissed as we are assured of the acceptability of “politics as usual.” Abroad, so-called “peace activists” armed with metal pipes and weapons are portrayed as the heirs of Martin Luther King and the non-violent protesters of Selma and Birmingham. Apologies are made for an American law approved overwhelmingly with the consent of the governed — to dictators who murder and imprison their own people on the merest of whim.

It is, in other words, just the moment to spend a quiet hour with the book that Jack Levin conceived and wrote a hundred years after the end of the Civil War. A small yet insightful volume that illustrates simply and vividly the timeless, two-minute address that Abraham Lincoln delivered in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 147 Novembers ago.

Mr. Levin, the son of immigrants, was twelve years old when, on July 4, 1937 he stood in the crowd of Philadelphians watching the city’s celebratory parade of the document that had its birth in nearby Independence Hall. One old man caught Jack Levin’s attention. Seated alone on the back of a convertible, dressed in the old blue uniform in which he had fought, sat a solitary veteran of the Civil War. It was 72 years after the close of the war that cost over 600,000 American sons their lives.

It was a sight the young Jack Levin would never forget, setting him on a course that would enable him to do two things. First, use his liberty in the pursuit of happiness, as Lincoln referenced the Declaration crafted in Philadelphia with the words “four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Second, Mr. Levin sought to bring to life for future generations the true meaning of Lincoln’s words with period illustrations and the stark, striking photographs of the day, Matthew Brady’s among them.

As his son Mark tells us, Jack made full use of the liberty of which Lincoln spoke. Over the course of his life Jack Levin learned to draw, design and invent. He worked in a cigar factory, sketched frames for furniture manufacturers and served in the Army Air Corps (underage when he signed up, he returned as soon as he turned 18). Disney accepted him as an illustrator — but his parents thought him too young, at 15, to head out to California on his own. He worked as a cartoonist, made displays for store windows, got a college education and, with his wife Norma, built and operated a small business, a pre-school and summer camp for kids. And took the time, of course, to be a father to his three sons.

Yet the image of that Civil War soldier so stayed with Jack that eventually he designed, illustrated and produced the book he had in his head — an illustration of the text of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. It was first published as the centennial of the Civil War came to an end.

“It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced,” said Lincoln, words Jack has paired with a photo of Union soldiers, standing at attention in the sun, blinking into the camera as they presumably wait for an order to move out, the living among the dead.

Unfinished work it was for the living of 1863 — and remains for the living of today and all the tomorrows yet to come.

The simple obviousness of new generations of Americans drives home the necessity of passing down to each the necessity to educate themselves in the basic founding doctrines and documents that have provided their ancestors with so much abundant opportunity. Like the young man Jack Levin there will always be young men and young women — the sons and daughters of America — who want the opportunity to follow their dreams as Jack followed his.

But without their equivalent of seeing that old soldier sitting on the back of a car in a Philadelphia Fourth of July parade, they — we — are terribly vulnerable to the arrogant assumption that liberty and freedom are a given. American ideals — the very heart of what allows so many millions of dreams to flower and flourish — come with a high price.

Sometimes, as in the case of the battles surely seen by that old Civil War soldier, the price is blood and treasure. Thankfully it is more often the hard work of a good education and hard work itself. Having an understanding of American history and exactly how and why a country committed to the ideals of liberty, equality and freedom was and remains unique — and being unique — prosperous.

Abraham Lincoln — he who never went to college yet had the basic grammar of America in his bones — understood this. Standing on that Gettysburg Battlefield in 1863, knowing the horrific sacrifices that had had been made on the ground before him– he used the opportunity to pledge ” that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Those words, eloquent, elegant, filled with meaning — are always in danger of losing their meaning if not understood, as Lincoln understood them, in the context of American history. The actual photograph Jack Levin includes of Lincoln presumably delivering his speech amid the chaos of a jostling, packed crowd in a day before electricity and microphones is a reminder of just how difficult it might have been in the day for those actually in attendance to understand the import of Lincoln’s words.

“We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution,” said Jack Kennedy, with the same thought in mind that Jack Levin would express in book form five years following JFK’s inauguration.

As Father’s Day approaches, along with yet another anniversary of those terrible three days between July 1 and July 3, 1863, Jack Levin reminds yet again of all the sons — and now too the daughters — who have sacrificed so much for all of us to live every single day in the peace of liberty and freedom that is America.

Reading Jack Levin’s book, and of his own story, I am reminded yet again of my own father, missing now his fourth Father’s Day but who, in his almost ninety years, imparted the same exact lesson to this son which Jack Levin did to his.

Liberty — freedom — is the charge of every American generation. Sometimes to secure it, always to protect it.

Book Review from The American Spectator, by Jeffrey Lord

Tags: Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address Illustrated, Jack E. Levin, Mark R. Levin

- The Author

Jack E. Levin

Jack E. Levin has been variously an author, artist, and small businessman. He lives in Florida with his wife of […] More about Jack E. Levin.

- Books by the Author