Absolute Power: The Legacy of Corruption in the Clinton-Reno Justice Department

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Lord Acton’s famous admonition underlies both the title and subtitle of this account of how President Clinton’s promised “most ethical administration” in American history came to include a politicized and corrupt Justice Department. Critical of Clinton and Janet Reno, his appointed attorney general to head the Justice Department, author and attorney David Limbaugh describes and documents their politicized corruption of the administration of justice.

The U.S. Constitution vests federal executive power in the president, who is under oath to execute the office faithfully and to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. Among the president’s constitutional duties, he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed. Underlying those constitutional provisions is the political philosophy of protecting liberty through the rule of law. As Limbaugh notes, the rule of law is the core maxim “that we are a government of laws, not men.” Accordingly, no man is above the law, and the law restrains the government itself. Nevertheless, what James Madison called “the great difficulty” remains: “You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Limbaugh ”bookends” his case against Clinton-Reno abuse of the governed with accounts of the Waco disaster and the Elián González abduction. At Waco, agents of the Clinton-Reno Justice Department executed a military-style seizure of a sect’s compound under the pretense of serving search and arrest warrants, resulting in the deaths of scores of American citizens including children. In Elián’s case, other Clinton-Reno agents executed a pre-dawn commando-style raid of an American home under the pretense of a search warrant to abduct a legal-alien child at gunpoint, resulting in his return to communist Cuba. In both cases, Clinton and Reno piously proclaimed the primacy of the rule of law, but, as Limbaugh demonstrates, the law required neither the Waco seizure nor the Elián abduction; they were Clinton-Reno decisions.

Between those bookends, Limbaugh chronicles the Clinton-Reno failure to apply the rule of law to themselves and their government. He shows how political expediency led Reno to abandon an earlier legal position and undertake unprecedented litigation against an American business, how opportunism and cronyism led to a conspiracy against innocent government employees, how the politics of personal destruction led to the release of an employee’s personnel records in violation of privacy protections, how far-fetched privilege claims were asserted to delay investigations, how administration lawyers ignored or avoided some Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution, and how Clinton granted clemency to terrorists in an obvious effort to bolster his wife’s senate campaign.

In Limbaugh’s most devastating accounts, he explains the Clinton administration’s compromise of American security in soliciting Chinese political contributions to his re-election campaign and how Clinton and Vice President Al Gore illegally raised political contributions. And he shows how Reno enabled them to avoid enforcement of the laws against them by preventing career Justice Department personnel from pursuing the matter under the pretense that it might become subject to an independent counsel—and then refusing to appoint an independent counsel. Limbaugh leaves no room to doubt that politics was often the deciding factor in Justice Department action or inaction.

The author exposes the Clinton-Reno “rule of law” as a pious pretense masking political opportunism and depending, to borrow Clinton’s infamous phrase, “on what the meaning of is is.” Americans who cherish their liberty under the rule of law should lament that more of us are not as concerned as David Limbaugh about the Clinton-Reno abuses. The politicization of the Justice Department is something much to be regretted, as it removes one of the obstacles to wrongdoing by the president and his administration. With the Justice Department in the hands of dutiful party men (or women), the executive branch is not “obliged to control itself.” Alas, Bill Clinton has now set a precedent in that regard.

Absolute Power is a polemic, however, and as the brother of Rush Limbaugh, the author is subject to familiar dismissal as just another “a Clinton hater.” That evasive tactic, however, should not dissuade people from reading this serious and well-researched book.

Book Review from The Freeman, by Arch Allen

Tags: Absolute Power: The Legacy of Corruption in the Clinton-Reno Justice Department, David Limbaugh

- The Author

David Limbaugh

** Exclusive CBC Author Interview with David Limbaugh ** David Limbaugh is a lawyer, nationally syndicated columnist, political commentator, and author […] More about David Limbaugh.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

VIP BONUS Episode – “One Last Thing” with David Limbaugh As He Discusses “Growing Up Limbaugh”!

Listen to our exclusive bonus podcast interview with David Limbaugh as he talks about growing up in the Limbaugh household! [...]

Ep. 38 – David Limbaugh Interview: How Did the Early Christian Church Form?

Our friend David Limbaugh is back in the CBC studios to discuss his new book, Jesus is Risen: Paul and[...]

David Limbaugh’s Top 5 Favorite Books Every Conservative Should Read

David Limbaugh, brother of Rush Limbaugh, is a bestelling author of Christian apologetics -- including The Emmaus Code and the[...]

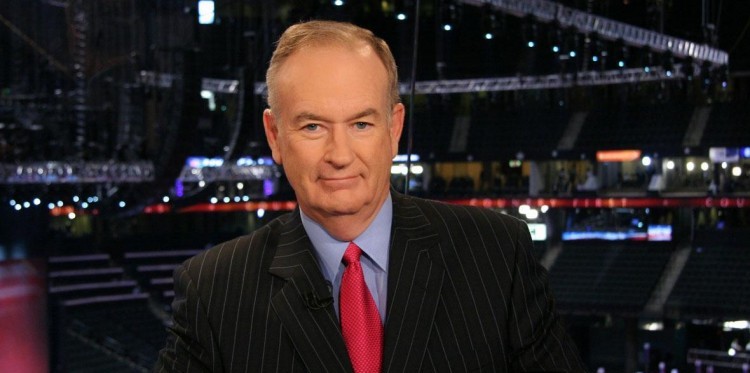

Bill O’Reilly Latest Victim of NYT “Best Sellers” List Deception

The NYT has been exposed once again for deceiving the American public with its hardcover nonfiction “Best Sellers” list -[...]

Limbaugh Brothers Dominate Conservative Bestseller List

The dynamic duo of this week’s Conservative Bestseller List are the Brothers Limbaugh - both landing a total of three[...]