The Conservative Revolution: The Movement That Remade America

In the prologue to his splendid History of the Hews, Paul Johnson explained that “Writing a history of the Jews is almost like writing a history of the world, but from a highly peculiar ingle of vision. It is world history seen from the viewpoint of a learned and intelligent victim…It adds to history he new and revealing dimension of the underdog.”

In a manner of speaking, what Paul Johnson did for the Jews, Lee Edwards has now done for American conservatives. His useful book, The Conservative Revolution, is basically a history of post- Norld War II American politics written from the “highly peculiar angle of vision” of the learned and intelligent victims of the dominant liberal historiography. By providing “the new and revealing dimension of the [conservative] underdog,” Edwards helps us see our recent past in a strikingly different light.

Consider, for starters, the presidency if Harry Truman. To me and a great many others, Truman is one of the great heroes of American history-the man who helped save Western Europe from Soviet domination. Domestically, however, Truman’s instincts were those of a left-wing populist, and as Edwards points out, he was not above demagoguery of Clintonian proportions, particularly when his opponents were right-of-center. During his 1948 presidential campaign against New York’s Governor Thomas E. Dewey, for example, “Truman presented to the electorate what can only be described as a deliberately false and mean distortion of the truth about Dewey, Taft, Hoover, Republicans in general, and the so-called do-nothing Eightieth Congress.. ..He gleefully smeared Dewey, charging that a vote for the New Yorker was a ‘vote for fascism.’… In Chicago, Truman went off the rhetorical chart by comparing the ‘powerful forces’ behind the Republican party to the interests that raised Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo to power. He said that what happened in Germany, Italy and Japan ‘could happen here’ if the ‘evil forces’ working through the Republicans triumphed.”

If Truman emerges from Edwards’s history with his halo askew, Congressman Joseph McCarthy comes off as a deeply flawed politician, but not someone who deserves the devil’s horns his liberal critics have successfully planted on him. Edwards essentially endorses the analysis of McCarthy’s closest aide, Roy Cohn, who admitted that his boss was “impatient, overly aggressive, overly dramatic,” but who nonetheless maintained that he was “right in essentials.” Certainly few can deny that the Government of the United States had in it enough Communist sympathizers and pro-Soviet advisers to twist and pervert American foreign policy.” (In 1977, when Cohn wrote these words, many did deny that the Roosevelt and Truman administrations were heavily infiltrated by Communists, but today, thanks in large measure to the revelations contained in the recently declassified Venona intercepts, such denials are increasingly rare.)

Edwards’s portrait of Richard Nixon is also unconventional. Nixon’s liberal critics often depict him as a conservative, but according to Edwards, Nixon was an opportunist whose only ideology was self-advancement. “Richard Nixon always knew where the power was,” he writes. “In 1960,he cut a deal with Nelson Rockefeller, the leader of the eastern liberal Republicans, to ensure his nomination for President. In 1968, he enlisted the support of prominent conservatives like Barry Goldwater, Strom Thurmond, and John Tower because the power of the GOP had shifted sharply to the right.” Yet after becoming president, Nixon “closed himself off from the conservatives who had nominated and elected him, preferring the counsel of big-government Democrats like former Texas governor John Connally and Harvard professor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and practitioners of realpolitik like Henry Kissinger.”

Not surprisingly, the two heroes of The Conservative Revolution- Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan-are hardly liberal icons. Goldwater’s great virtue, according to Edwards, was his selfless sense of duty. He knew he couldn’t beat the wily and duplicitous Lyndon John- son in the 1964presidential race, but felt he owed it to his fellow conservatives to make a run anyway:

It was an unprecedented act in American politics. Never before had a presidential candidate run knowing beyond any reasonable doubt that he could not win the general election. That hard reality accounted for the grim face and voice over the next eleven months (no one enjoys committing political suicide), the uncompromising content of his speeches and positions (he would give the voters a real choice), and the all-Arizona composition of his campaign team (it was the last wish of the condemned politician to be accompanied by his closest friends as he went before the firing squad).

Goldwater lost to LBJ by a landslide, yet his campaign served to introduce the nation to a new political star. A week before election day, Ronald Reagan delivered a nationally televised address on Goldwater’s behalf that raised millions of dollars for the beleaguered Arizonan and set the stage for his own successful gubernatorial bid in 1966. Goldwater, however, never even sent Reagan a thank-you note. “Apparently,” writes Edwards, “for one of the few times in his life, Goldwater dis- played jealousy, especially when some conservatives, after seeing Reagan on television, suggested that maybe the wrong conservative had been nominated.”

The inauguration, on January 20,1981, of Ronald Reagan as the fortieth President of the United States ushered in what Edwards calls the “Golden Years“ of American conservatism. Reagan won the presidency because “he was a man with an idea whose time has come. The idea was that government had grown too big and should be reduced, and America’s military had grown too weak and ought to be strengthened.” At home, Reagan’s fidelity to his core beliefs led to a tremendous outburst of economic growth; abroad, it brought down the seemingly invincible Soviet empire.

Yet conservatives today tend to look back on the Reagan presidency through rose-tinted glasses. Edwards reminds u s that relations between President Reagan and the conservative movement were not all sweetness and light. On the domestic front, conservatives complained that for all his fine rhetoric, Reagan had left the basic structure of the Great Society firmly intact. In foreign affairs, Reagan’s decision to sign the INF treaty with Moscow and his public avowal that Gorbachev’s Soviet Union was not the “Evil Empire’ of yesteryear, were widely resented, with conservative activist Howard Phillip: going so far as to call Ronald Reagan ‘‘a useful idiot for Kremlin propaganda.”

With Reagan’s departure from the historical scene, relations between the various conservative tribes have sharply deteriorated. As Edwards writes, “Traditional conservatives, libertarians, neoconservatives, and social conservatives began fussing and feuding like so many Hatfield: and McCoys. They missed the soothing presence of Ronald Reagan and the unifying threat of communism. As soon a: the Berlin Wall came down, conservatives immediately began building walls between one another. Just four years after Reagan’s departure, there was open tall of a ‘conservative crackup.’ Editor-columnist R. Emmett Tyrrell wrote scathingly about organizations multiplying by the dozens to promote ‘The Supply Side Of Our Judeo-Christian Heritage! The Black Tie Fund-Raising Banquet!”’

Edwards rightly deplores these trends but does not believe that they constitute a major threat to the future of conservatism. Pointing to the impressive number of conservative think tanks, magazines, and talk shows that dot the land he concludes that “the conservative revolution is here to stay.” But do the numbers attest to the viability of the conservative revolution, or to the fact that conservatism has become less of a fighting faith and more of a mainline church; Could Lenin have been correct when he declared, apropos of revolutionaries “Better less, but better”? Unfortunately, these are questions that Edwards never raises. He does, however, convey a vivid and unapologetic sense of the world as seen through conservative eyes and in America’s prevailing climate that is indeed an eye-opener.

Book Review from The American Spectator, by Joseph Shattan

Tags: Lee Edwards, The Conservative Revolution: The Movement That Remade America

- The Author

Lee Edwards

** Exclusive CBC Author Interview with Lee Edwards ** Lee Edwards is the Distinguished Fellow in Conservative Thought at The Heritage Foundation. […] More about Lee Edwards.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

The Conservative Movement’s Leading Historian

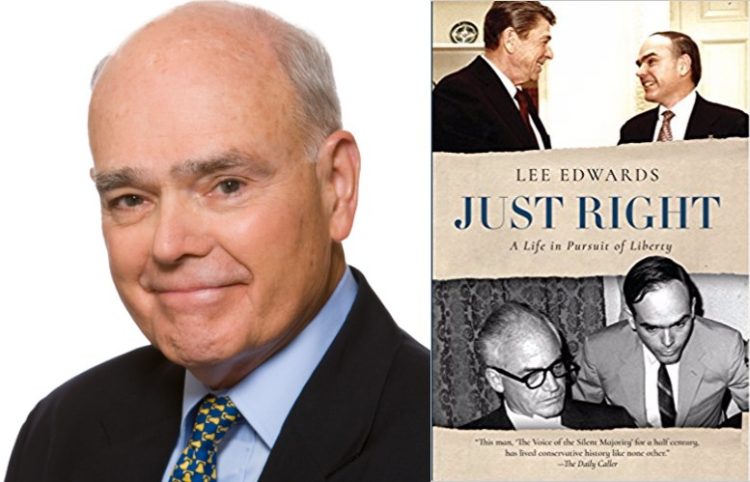

The conservative movement's leading historian, Dr. Lee Edwards, discusses his new autobiography book, "Just Right: A Life in Pursuit of[...]

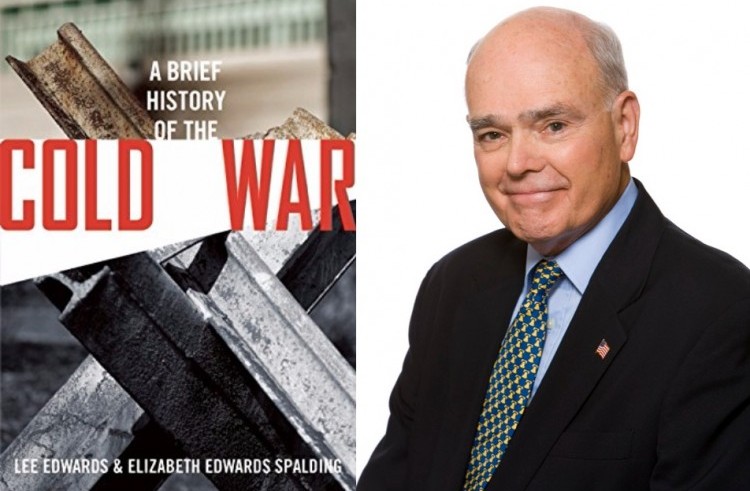

A Brief History of the Cold War (Author Interview: Lee Edwards)

Dr. Lee Edwards, the Distinguished Fellow in Conservative Thought at The Heritage Foundation, is interviewed about his recent book, "A[...]

CBC Profiled in The Daily Signal

Lee Edwards, distinguished conservative historian, and his wife, Anne Edwards, first employee of CBC, wrote a beautiful tribute about CBC.

Ratings Details