We Have Not Yet Begun to Fight for Digital Privacy

Original op-ed by Grace Houghton: Even though the Supreme Court ruled to protect your cell phone location information by a warranty under the Fourth Amendment, the fight for digital privacy has only just begun.

If we ignore the dissenting voices in the Supreme Court’s decision on Carpenter v. United States, we lose the opportunity to prepare ourselves for a conversation about digital privacy that is both complex and urgent.

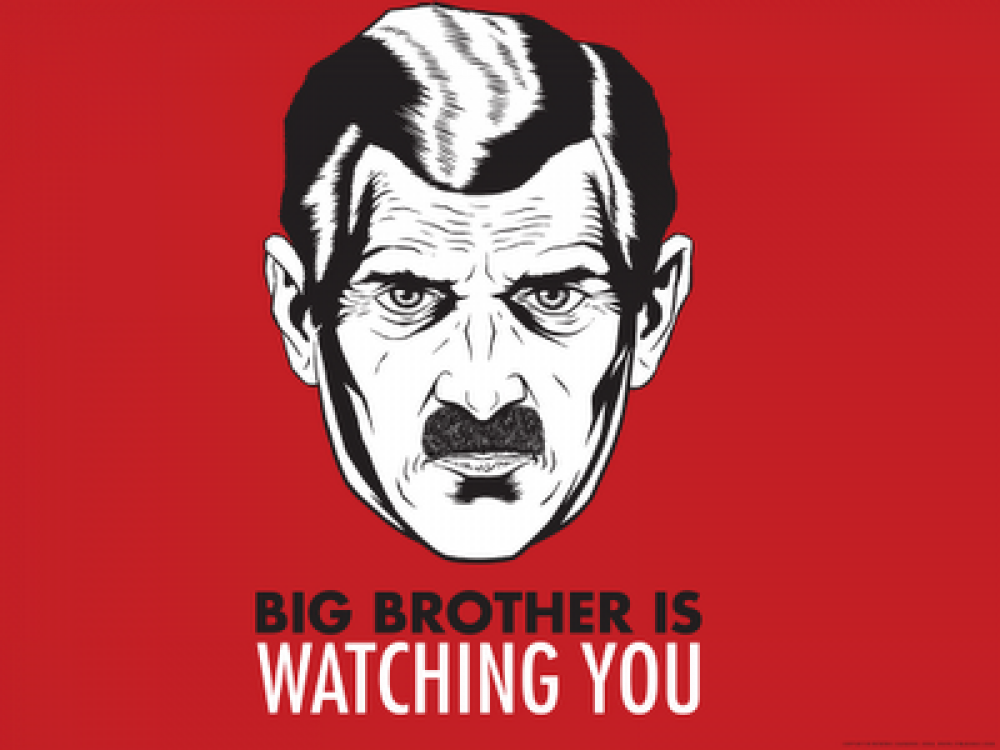

We have not yet begun to fight for digital privacy, and, like John Paul Jones, we’ve got some massive holes blown through our security already. We volunteer our location down to a matter of feet on our phone apps. We give obscure websites our grandmother’s name on a quiz to find out which celebrity is our spirit animal. Traffic cameras and CCTVs watch us constantly, in and out of the assumed privacy of our cars.

The Facebook Cambridge Analytica controversy recently exposed how undereducated we are about the privacy risks inherent in our daily lives. Are we desensitized to strangers knowing our favorite shopping websites and movies better than our friends do?

Are we bothered that we don’t know how to control our own privacy?

Mr. Carpenter, though convicted for stealing cell phones (of all things), demanded that the location data, gleaned by Sprint from his cell phone and subpoenaed by the government in his trial, be protected by the Fourth Amendment.

Because the Constitution does not directly address privacy, but only protects “persons, houses, papers, and effects” in the Fourth Amendment, the Court reached for a slippery definition of privacy established in an earlier privacy case, Katz v. United States.

Katz coped with technology’s attack on privacy in 1967 by expanding the Fourth Amendment to protect not simply you, your house, and your stuff, but to protect anything and any place in which you have a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” In a comforting, catchy phrase, the justices in Katz chose to protect “people, not places.”

The court has since used this ruling to limit wiretaps, GPS, and thermal imaging, and now, cell-site location information gathered by your cell phone company.

All good, right?

It’s easy, given everyone’s craving for assured privacy, to breathe a sigh of relief. “Protecting the people – it’s what the government should have been doing all along!” you might say.

In an atmosphere of relief and victory, we pass over the four dissenting justices: Justices Gorsuch, Alito, Kennedy, and Thomas.

If we do take notice of them, it’s easy to dismiss the dissenting justices based on political persuasion or on technique. Justice Thomas says privacy isn’t mentioned in the Fourth Amendment? Of course – he’s such a textualist.

“People think of court decisions like horse races. Who won and by how much?” said Kevin Daley, Supreme Court reporter for the Daily Caller News Foundation.

What is more difficult – and yet more productive – is to value the experience, wisdom, and office of each member of the court regardless of minority or majority.

Roberts, who wrote the opinion of the court, relied heavily on Katz’s criteria of “a reasonable expectation of privacy” to place cell-site location records under the protection of the Fourth Amendment.

Justice Gorsuch pointed out “…we still don’t even know what the “reasonable expectation of privacy” test is.”

While leaving things up to judicial intuition is a valuable tool for navigating grey areas, the court in Katz provided no black-and-white reference points.

Dissenting Justice Gorsuch actually suggested a stronger way for Carpenter to make his case.

“Plainly, customers have substantial legal interests in this information, including at least some right to include, exclude, and control its use. Those interests might even rise to the level of a property right.”

But because Carpenter didn’t “invoke the law of property,” and instead relied on the “reasonable expectations” argument of Katz, Gorsuch “cannot help but conclude—reluctantly—that Mr. Carpenter forfeited perhaps his most promising line of argument.”

Justices Gorsuch, Alito, Kennedy, and Thomas didn’t vote “no” because they dismiss the value of digital privacy.

Instead, the dissenting justices demanded the argument for the protection of cell-site records digital privacy under the fourth amendment to be watertight. Each found leaks in the majority’s reasoning.

Since the Fourth Amendment was originally meant to protect your property, Justice Thomas’s dissenting opinion analyzed whether the location information about Carter, which Sprint gathered and held, was actually Carter’s property.

“The Government did not search Carpenter’s property,” decided Justice Thomas. “He did not create the records, he does not maintain them, he cannot control them, and he cannot destroy them.”

Cases based on the Stored Communications Act (United States v. Miller (1975) and Smith v. Maryland (1979)) hold that “individuals lack any protected Fourth Amendment interests in records that are possessed, owned, and controlled only by a third party,” as Justice Kennedy writes in his dissent.

Based on this law, the U.S. government in Carpenter got Carpenter’s records from Sprint with a subpoena and not with a warrant. Rather than prove probable cause for Carpenter committing the crime, the government had only to prove the records relevant to the trial in general.

Chief Justice Roberts refused this “mechanical” application of the third party doctrine to Carpenter’s case because the records from Sprint contained a “qualitatively different category” of information than general location data. Cell-site location information is “detailed, encyclopedic, and effortlessly compiled,” and represents “near perfect surveillance,” he continued.

Privacy is near and dear to the conservative heart. Giving more responsibility to the government is not. Perhaps it’s worth asking: do we really want the government to take responsibility for our digital privacy?

The risks and the benefits of technology create great tension.

Modern society, with its immediacy, convenience, and availability, wouldn’t exist without cell phones – and the security risks inherent in their technology. ”[C]arrying one is indispensable to participation in modern society,” writes Chief Justice John Roberts in the opinion of the court.

And yet, as Justice Alito observes, “some of the greatest threats to individual privacy may come from powerful private companies that collect and sometimes misuse vast quantities of data about the lives of ordinary Americans” – and those private companies make our iPhones work.

“If today’s decision encourages the public to think that this Court can protect them from this looming threat to their privacy, the decision will mislead as well as disrupt,” continues Justice Alito.

We need clearer, more specific and objective tools than the “reasonable expectation of privacy” criterion that Katz provides. Did the court decide on those tools in Carpenter? No. As a result, lower courts will drown in nuance before they determine how to protect digital privacy.

Despite the triumphant tone of Carpenter, we are not fully equipped to fight for our privacy – and if we let the dissenting voices in Carpenter disappear, we risk losing the battle.