A Star in the East: The Rise of Christianity in China

Common wisdom and current trends show that Christianity is growing in traditionally non-Christian Asia and in Africa even as it withers away in Europe. The case of Christianity in China is especially interesting — the faith has established a foothold despite the Communist regime and decades of state repression. In their new book, A Star in the East, Rodney Stark and his protégée, Xiuhua Wang, tell a succinct, readable, and statistics-packed account of where Christianity has been in China and where it is likely headed.

A major strength of the book lies in its statistics. Assertions are backed up with data and graphs, despite the difficulties of obtaining data, seeing as the Chinese are more reticent about publicly admitting their religious convictions. Having presented their case, the authors feel justified in declaring that a “religious awakening” is taking place in China.

This would have seemed absurd 100 years ago; China seemed like a model agnostic and secular society.. Older missionary activity in China was thought to have produced little lasting results, despite a centuries-old Catholic presence and the syncretic, semi-Protestant fervor of the Taiping Rebellion. Our authors quip that instead of religion being the opium of the people, “faith in a coming post-religious China was revealed as the opium of Western intellectuals.”

Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution of 1966, which banned all religion and foreign influences, drove the faith underground but did not succeed in killing it. Christianity survived the cruelest repression and persecution, with churches burned, believers forced to worship in secret “house churches,” and thousands of clergy jailed or sent to re-education camps.

It should be mentioned that A Star in the East has a solidly ecumenical outlook; the authors give Catholicism and Protestantism equal attention, underlining the different dynamics of the two forms of Christianity when confronting Chinese culture. Before the Communist revolution, Catholics outnumbered Protestants three to one. The situation is now reversed. Catholic missionaries had a substantial head start in China, and the people could easily relate to Catholicism’s hierarchical and ritual aspects. But these same qualities, and the fact that Catholics owe allegiance to a “foreign ruler” (the pope), became disadvantages once Christianity went underground. In an attempt to keep the Christians under government control, the communists established approved religious bodies.

The fourth chapter is particularly interesting in its analysis of the class dynamics of Chinese Christianity. The data shows that the educated middle class tends to convert in greater numbers. In making this argument, Stark and Wang do good work in debunking the old “deprivation theory” about religion – the theory that people seek out religion primarily as a relief for their material misery. Our authors argue convincingly that it is social ties which are the decisive factor in influencing Christian conversions in China.

The authors also make a profound point regarding the clash between tradition and modernization in China: it is precisely a culture like China’s that reveres the past and lacks the modern western belief in inevitable “progress” that is likely to experience a spiritual void when the traditional features of the culture are excised (as they were under the Cultural Revolution). For many of China’s more educated citizens, Christianity has filled this void. This whole discussion proves to be one of the most intellectually stimulating parts of the book.

In the final chapter, the authors make some cautious predictions about the future of Christianity in China. As of now, tens of millions of Chinese have embraced Christianity, thousands more convert every day and more than forty new churches open every week. If these trends continue, then by 2030 there will be more Christians in China than in any other nation.

Most startling among the recent statistics is that a substantial number of Communist party members are now Christians. Stark and Wang speculate that Chinese Christians may play a role in helping tilting China closer toward democracy and the free market. As the authors state, “We shall have to wait and see” – a prudent conclusion to a well argued and highly informative book.

Original CBC review by Michael De Sapio

Tags: A Star in the East, China, Christianity, Rodney Stark

- The Author

Rodney Stark

Rodney Stark grew up in Jamestown, North Dakota, and began his career as a newspaper reporter. Following a tour of […] More about Rodney Stark.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

Ep. 38 – David Limbaugh Interview: How Did the Early Christian Church Form?

Our friend David Limbaugh is back in the CBC studios to discuss his new book, Jesus is Risen: Paul and[...]

Who Will Win the Most Medals at the Olympics?

The 2018 Winter Olympics have begun! Who do you think will win the most metals this year? Will Russia try[...]

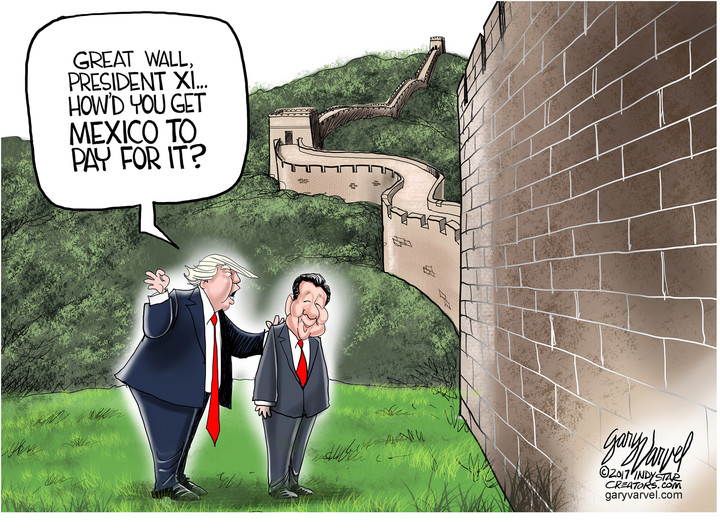

How Did Mexico Pay For China’s Great Wall?

Pres. Trump is currently on a diplomatic mission to China. See what he said about Great Walls to Chinese President[...]

Is The Media Being Hypocritical About Trump’s Taiwan Call?

"It’s a little mystifying to me that President Obama can reach out to a murdering dictator in Cuba in the[...]

Ted Cruz Calls Out Obama For Being An Apologist For Islamic Terrorism

"Now last I checked the Crusades ended 900 years ago. I don’t think it is asking too much to ask[...]