Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution

“Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice, and moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” This line—perhaps the most famous of any presidential convention speech—was Barry Goldwater’s 1964 call to shake off the dusty doctrines of the New Deal and rediscover the beauty and vitality of the American ideals.

While he lost that election, the late Senator from Arizona gained something much more an important—a place for conservatism in America’s future. According to author and historian Lee Edwards, “No presidential candidate Goldwater, no President Reagan.” His book, Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution, examines Goldwater’s unparalleled impact on the conservative movement in America.

Like many Americans of his time, Barry Goldwater was a conservative, although many other Americans didn’t realize their own beliefs. As his own thinking matured as a Phoenix businessman and civil servant, he was persuaded to make a seemingly impossible run for an Arizona Senate seat as a Republican. But Goldwater didn’t care about the odds. He cared about the principles. And he also knew that like him, most of the Arizonans who voted overwhelmingly Democratic were conservatives who just didn’t know it.

Of course, it didn’t hurt that soon-to-be President Eisenhower was swept into office in a rout that dragged Goldwater into office by his coattails. As a new senator, Goldwater astounded colleagues and observers alike for his principled stands, eloquent defense of conservatism, and ability to raise money and popular support for Republicans. He even fought for liberal Republicans, believing that that the GOP, as the historic home for conservatism, must be preserved and promoted.

At the same time Goldwater would not allow the liberal Republicans of the eastern establishment to continue their stranglehold on the party. As a result, Goldwater reluctantly gave in to the demands and drafting effort of thousands of young conservatives across the country, and threw his hat into the ring for President.

Lee Edwards examines all of these facets of Goldwater’s early career thoroughly, building the case for Goldwater as a seminal figure to the conservative movement. Edwards then moves onto Goldwater’s growing popularity.

Many young conservatives fell in love with Goldwater for his instant classic—and perhaps the most influential political treatise of the 20th century—The Conscience of a Conservative. Besides being a treatise for conservatism, Goldwater gave voice to a popular yearning for liberty by reminding Americans that “A government that is big enough to give you all you want is big enough to take it all away.” Americans didn’t need a New Deal, but a new appreciation for the Constitution.

Goldwater’s book, and his candidacy, showed that the New Deal had not created a new consensus and that the country need not continue on its steady slide toward socialism. In Goldwater, conservatives believed they finally had a man who could win back the GOP, the presidency, and the hearts and minds of the people.

Everything came crashing down on the day JFK was assassinated. Republicans would be running against the invulnerable ghost of JFK, rather than the much more vulnerable president. They also would have to square off against Lyndon Johnson, a man utterly devoid of principles.

But that was only the beginning of the pain for Goldwater. Liberal Republicans, like Governor Nelson Rockefeller, refused to cede the party to the “extremists” on the right. As Goldwater edged closer to the GOP nomination through vast grassroots support, the liberals within the GOP became vicious—parroting mainstream media myths of Goldwater’s likely recklessness with “the bomb,” his desire to destroy social security, and his disdain for civil rights. After Goldwater was nominated, many refused to back him in the general election against LBJ.

Imagine a campaign commercial that began with a little girl plucking flower petals while counting to ten, then hearing a sinister voice count down from ten, following by footage of a nuclear detonation. The reprehensible campaign of LBJ was symbolized in that famous commercial. He put out these commercials, already knowing that he would win by a landslide. He just wanted the biggest landslide in history.

Goldwater was crushed in the 1964 election by Johnson, winning only a handful of deep southern states in the process. Yet it was a pyrrhic victory for the Democratic Party. Johnson would become ensnared in his own lies regarding Vietnam, and the electoral landscape changed dramatically as a result of Goldwater’s efforts. The conservative movement had retaken the GOP and was continuing to grow throughout the country, and for the first time, the south had turned to the GOP—finally making it a national party.

That Ronald Reagan also gave his famous “Time for Choosing” speech in the final week of the campaign—a speech that electrified conservatives around the country and got Reagan elected as governor of California two years later—was just icing on the cake.

While Goldwater is known primarily for pulling the conservative movement up by its bootstraps in 1964, he made serious mistakes later in his career. He supported President Ford—a clear moderate—over Reagan in the GOP presidential primary in 1976, likely winning the race for Ford. He also profoundly disappointed conservatives by opposing the Moral Majority, vacillating on social issues until he clearly came out in favor of abortion and LGBT issues in the 1990s.

Yet our heroes truly earn their esteem once their capes come off. Goldwater was not a perfect man,, but he was indispensable to the conservative movement. George Will described him as ‘a man who lost forty-four states but won the future.” Even the leading conservatives on the 90s, having received his vitriol, refused to repay it. As Richard Viguerie wrote at the time, “Conservatives will never be able to repay their debt to Goldwater.”

The conservative comeback after the New Deal required lone philosophers, like F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Russell Kirk, to establish it, and a popular magazine, National Review, to bring these intellectuals together and publicize their views. It took a politician like Goldwater to put the movement back on the map. “Mr. Conservative” may not have brought the GOP into the White House in 1964, but he made the Republican Party a national party, a conservative party, and through his successor at the helm of the movement, Ronald Reagan, a victorious party.

With eyes to the election of 2016, let us lift up the legacy of Goldwater and renew his dream of an ascendant conservatism, and with it, an ascendant America.

Original CBC review by Stephen Roberts

Tags: Barry Goldwater, Goldwater: The Man Who Made A Revolution, Lee Edwards

- The Author

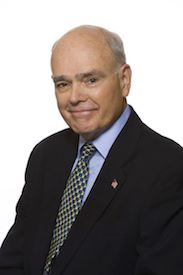

Lee Edwards

** Exclusive CBC Author Interview with Lee Edwards ** Lee Edwards is the Distinguished Fellow in Conservative Thought at The Heritage Foundation. […] More about Lee Edwards.

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

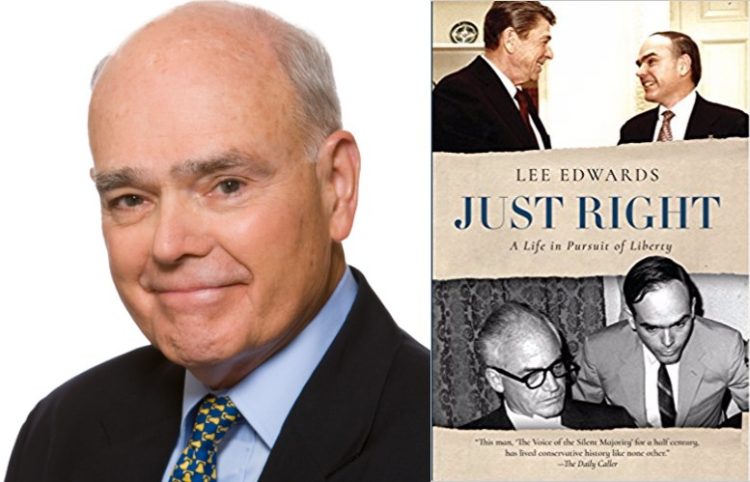

The Conservative Movement’s Leading Historian

The conservative movement's leading historian, Dr. Lee Edwards, discusses his new autobiography book, "Just Right: A Life in Pursuit of[...]

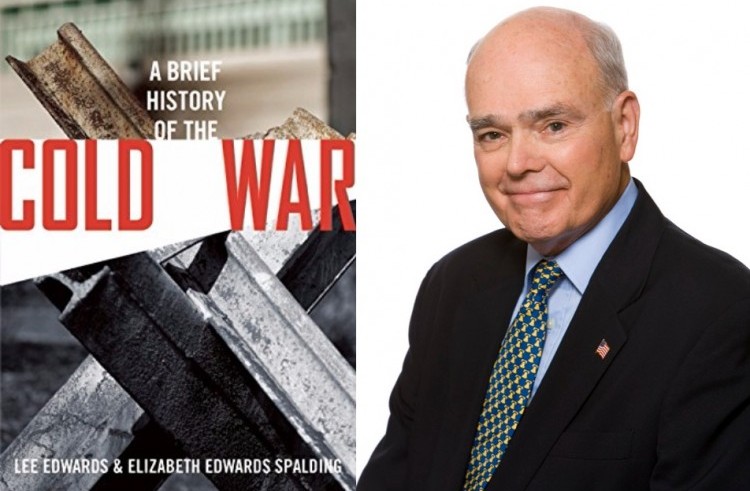

A Brief History of the Cold War (Author Interview: Lee Edwards)

Dr. Lee Edwards, the Distinguished Fellow in Conservative Thought at The Heritage Foundation, is interviewed about his recent book, "A[...]

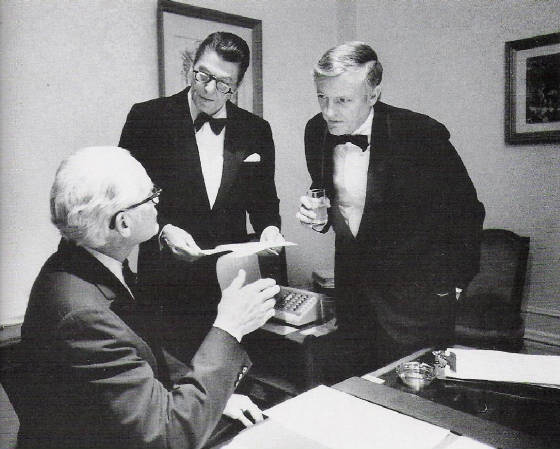

Throwback Thursday Picture of the Week

A rare candid moment of three giants of the conservative movement, including Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, and William F. Buckley,[...]

CBC Profiled in The Daily Signal

Lee Edwards, distinguished conservative historian, and his wife, Anne Edwards, first employee of CBC, wrote a beautiful tribute about CBC.

Ratings Details