Keeping the Tablets: Modern American Conservative Thought

This is a revised edition of the col- lection William F. Buckley, Jr. published in 1970under the title American Conservative Thought in the Twentieth Century. Only 30 percent of the 1970 essays survive. But the twenty-six essays that make up Keeping the Tablets address the same mat- ters, which preeminently include the limits of the state and the threat of Communism. As he title suggests, this is not a book about policy prescriptions but first principles-what you’d find engraved in stone.

Buckley and his coeditor, Charles R. Kesler, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College, deserve credit for bringing out this volume at appropriate time for conservatives, as

Kesler puts it in his introduction, to reacquaint themselves “with the paradigms of conservatism, to revisit the insights that first gave rise to the conservative movement and that have guided the rhetoric of the Reagan administration.

This is also a good time to be pondering the future of conservatism, and Keeping the Tablets is useful in this regard. The essays collected here not only state first principles but also show that conservatives are seriously divided on some basic propositions.

There is a group of conservatives, represented in this volume by Willmoore Kendall, who are not enthralled with the Declaration of Independence and its understanding that “all men are created equal.” These conservatives champion states’ rights, are wary of the Fourteenth Amendment, and come close to endorsing pure majoritarianism. Some of the conservatives in this group seem at times more English and European than American; they are more conversant with Edmund Burke, for example, than with George Washington or James Madison.

In very clear disagreement with this group is another, represented here by Harry V. Jaffa (who appears twice in this volume), whose understanding of the American experiment is grounded in the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence. For these conservatives, the union preceded the states, the Fourteenth Amendment is hardly anathema, and pure majoritarianism is inconsistent with the very principles by which our political society has been organized. These conservatives seem much more at ease with the American political tradition.

The differences between Kendall and Jaffa, Kesler’s philosophical mentor, have appeared politically during the Reagan years, in personnel selections as well as policies. But as Kesler understands, conservatives face a choice in these matters. He comes down, as I do, with Jaffa or, more precisely, with the Declaration of Independence and its teachings. “There is no substitute for the faith of our fathers,” he writes. “If the Declaration of Independence is not American, then nothing is.” The Declaration supplies the moral principles, he says, that prudence then may serve.

This is not .the place to advance the many reasons why Kesler is right, only to observe that his thinking has important practical consequences. He argues that the moment American conservatism fully embraces the political teaching of the Declaration it will be more able to speak “the vernacular of American politics.” It will thus begin to shed its status as a “movement” (which many conservatives are rightly proud of but whose persistence confirms its parochial character). And, he goes on to say, if conservatism understands, as progressivism did at the turn of the last century, the importance of political parties, it will reconstitute the Republican party by having it raise “fundamental questions of justice and the common good that lie at the heart of politics.” These include such questions as the unjustness of progressive taxation, the danger to everyone’s rights posed by quotas and other racial preferences, and the importanceof the Strategic Defense Initiative as the only plausible means of fulfilling the constitutional responsibility to protect the nation.

Kesler’s introductory essay should be read and reread. But there are related issues that neither he nor the contributors to Keeping the Tablets adequately explore. One is the role of the courts in our society. Walter Berns brilliantly demonstrates how Oliver Wendell Holmes provided the theoretical groundwork for judicial activism as well as for what Kesler calls “the positivist version of judicial restraint.” Kesler parenthetically explains this as “deference to legislative majorities without any higher law limitations,” but more discussion of the deeper issues involved would have been fitting in this volume For example, conservatives divide on the question of whether judges should invoke “higher law limitations” that have not been expressed in positive law. Should judges say the Constitution protects the right to life of the unborn even though the Constitution does not mention that? Meanwhile, conservatives of varying points of view are busy working out theories of legal interpretation. For example, there is the Law and Economics school, perhaps best represented by Richard Posner, a Reagan appointee on the US. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. There are those who seek to discern the “original meaning” of the law. An essay on legal interpretation would also have been appropriate

So too would have been at least one essay on the very difficult problems of cultivating virtue in a society that celebrates liberty and sometimes gets it confused with license This problem involves a complex of issues, including the roles of religion, family, and community. (One of the best essays on the subject, incidentally, was Irving Kristol’s “Republican Virtue vs. Servile Institutions,” published in the February 1975 issue of The American Spectator.)

Finally, it’s worth noting that Keeping the Tablets includes four essays on Communism that illustrate conservative unanimity on at least one matter. The pieces by Gerhart Niemeyer and James Burnham are separated in time by at least fifteen years from those by Norman Podhoretz and Jeane Kirkpatrick. But all of them are agreed on the evil of Communism. Despite apparent changes in the Soviet Union, the underlying reality of Soviet ideology remains the same. For contemporary evidence of what can result from Communism the world has only to look at Ethiopia.

Niemeyer’s essay on the “Communist mind” is as cogent and insightful as you will find (“Communist totalitarianism springs from the arrogation of the role of God,” he writes.) And Burnham’s contribution, reprinted from the 1970 volume, wears well. In one striking sentence, he makes the ultimately important point: “So long as we are willing to include death among possible alternatives, we shall always be free to choose.”

Keeping the Tablets closes, as the earlier volume did, with essays by Whittaker Chambers and Albert Jay Nock on “The Spiritual Crisis.” These are eloquent reminders of the spiritual dimension of much conservative thought. This dimension has not, for all conservatives, been Christian, or even monotheistic. But whatever its character, it has provided conservatives with some degree of serenity in what Buckley calls “this dreadful century.” In reminding us that this world is not all there is, Keeping the Tablets keeps the most important tablet of all.

Book Review from The American Spectator, by Terry Eastland

Tags: Keeping the Tablets: Modern American Conservative Thought, William F. Buckley

- The Author

William F. Buckley, Jr.

William F. Buckley, Jr. was the renaissance man of modern American conservatism. He was the founder and editor in chief […] More about William F. Buckley, Jr..

- Books by the Author

- Related Articles

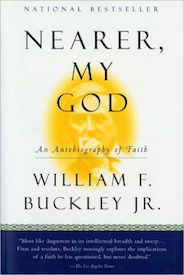

Interview with Fox News’ James Rosen About Bill Buckley

James Rosen, Fox News' Chief Washington Correspondent and bestselling author discusses his new book, "A Torch Kept Lit: Great Leaders[...]

Deceased Legendary Conservative Author William F. Buckley, Jr. Makes Conservative Bestseller List

Even in death, William F. Buckley, Jr. – the early leader of the burgeoning conservative movement, lands on the Conservative[...]

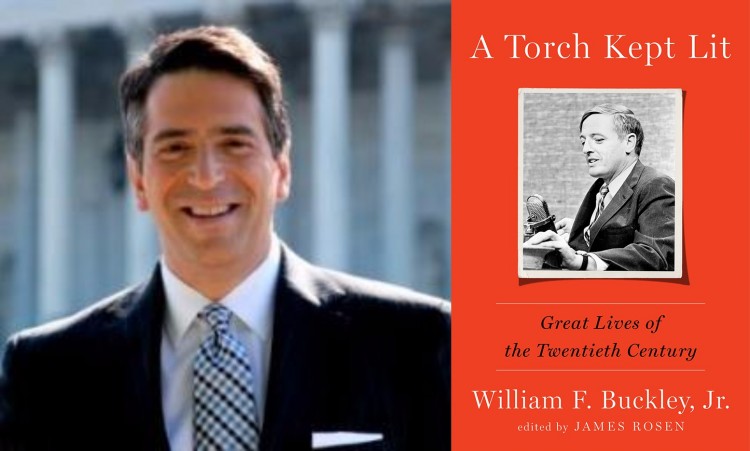

William F. Buckley – A Profile of the Most Consequential Conservative (Interview: Heather Hendershot)

In a fresh take on William F. Buckley, Jr., the preeminent leader of the early conservative movement, author Heather Hendershot[...]

National Review Comes Out “Against Trump”

National Review, the flagship conservative magazine started by conservative icon William F. Buckley, Jr, has released their latest issue of […]

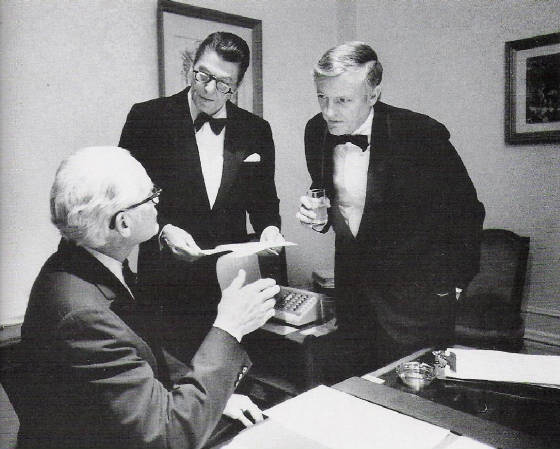

Throwback Thursday Picture of the Week

A rare candid moment of three giants of the conservative movement, including Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, and William F. Buckley,[...]